By Tom Lowe

Motivating students to attend and engage in higher education has been a common theme throughout this blog series. My previous blog talked about the importance of getting our learning spaces right to foster student engagement and community, which is certainly part but not all of the picture with regards to improving student attendance. The next two blogs in this series will talk about what we choose to do with that precious classroom contact time when we have it. Today I will shift in focus slightly to discuss the agenda of ‘embedding’ employability into the curriculum – what this means and how we might go about doing it. With increasing numbers of students reporting that they have to work to support their studies (leaving less room for extra-curricular endeavours) and the societal trends in engagement leaning towards online digital engagement, the graduate outcomes agenda placed upon universities is increasingly shifting focus towards positioning the curriculum as a means to engage students with building employability skills. Whether you call it ‘embedding’, ‘integrating’, ‘baking in’, or making it ‘structurally unavoidable’, making employability part of the course is a hot topic of focus in the higher education sector.

The disciplinary content packed into well designed, coherent, research-rich and subject-specific courses means there is often little room for simply adding new material into a programme. Each of these modules will assess students on a range of required learning outcomes through methods such exams, essays and presentations, and more recently, innovative workplace-related authentic assessments. The assessment regime is then complemented by taught sessions in a range of formats, e.g., lectures, discussions and practical-based timetabled classes. The assessment and teaching experience connected with the learning outcomes all work together to support the knowledge and skills development required for the degree. So what does it mean to steer away from disciplinary knowledge and skills, and think more about employability?

Traditionally, degree programmes have operated in a relatively strict ‘disciplinary’ realm, with History degrees focusing on History, Nursing focusing on Nursing, and Business Management on Business Management. With the sector turning towards employability metrics, stimulated in the main by regulatory requirements, these disciplinary spaces are being asked to support more topics, often outside of their particular specialist academic fields, such as application writing for graduate jobs, career planning, and interviewing skills – activities that often engaged students outside of class. Herein lies the tension. With the pressure to work alongside their degrees taking students away from extra-curricular self-developmental activities, academics are being tasked with ensuring exposure to professional development, employability skills, are encountered within the timetabled sessions… However, in order to bring this in, other (disciplinary) content must be taken out and colleagues are having to learn more about employment beyond academia. But why should we do this? Let’s explore this question, as it’s one I often find myself answering when advocating for embedding employability into the curriculum.

Don’t all degrees lead to graduate jobs?

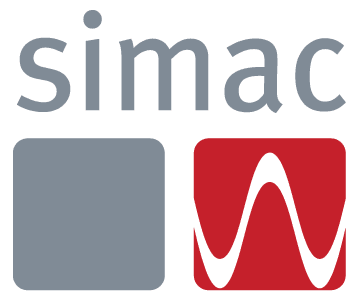

This blog will outline two scales of consideration when looking at the notion of improving employability in higher education. Both will support the need to embed employability into the curriculum (and assessment), but for two very different reasons and with perhaps different actions required. To help frame this discussion, first, we should turn to consider the level of direct vocational focus of the individual degrees we are looking at to improve graduate outcomes on, as the need to embed employability will vary from course to course.

On one end of the below scale, you will have degrees that are highly vocational and often written to meet the requirements of a certain profession (usually these courses are accredited by a professional body). In some instances, there is also a very high societal need for these vocational courses (think Nursing, Primary Teaching) and the labour market is desperately seeking graduates of these courses. At the other end of the scale, are courses that are rooted in disciplinary (and perhaps more traditional) studies where beyond being a teacher or lecturer in those disciplines, there are very few paid graduate roles specifically made for graduates in that area beyond academia - as much as it would be marvellous to have a whole labour market for the role of ‘philosopher’ or ‘historian’. This is not to disregard the societal need for these graduates and the variety of transferable skills these students acquire – I am a graduate of a History and Archaeology degree and I know first-hand that many of the skills acquired through these courses transcend disciplinary fields - but simply to outline the direct links to the labour market are not so clearly set out for these programmes. When thinking about embedding employability for your course, first try thinking about job market demand for the degree on this scale to prompt thinking about the labour market and the graduates your course is producing.

When considering what to embed to vocational or more discipline-specific degrees, there will be different considerations depending on your overall goal. For example, when running a Primary Teaching degree, the embedded employability activities are often threaded throughout the placements and portfolio assessment, but can also focus on the job application routes common with that profession. For the programmes that focus on an industry, but with different roles available across different sectors (such as marketing), there could be a whole variety of topics to cover such as career planning and employer awareness. For disciplinary degrees that don’t link directly to a large graduate industry, a greater focus on translating skills learned on the course to a variety of different industries will be more worthwhile, to increase students’ understanding of how their skills can be applied to a diversity of workplaces. It’s worthwhile highlighting at this point that this translation and articulation of skills is really the key here, as 84% of graduate roles did not ask for a specific degree (HEPI, 2023).

‘I studied a traditional degree, and I got a graduate job’

You may be reading this having studied a traditional academic subject with no embedded employability, and thinking to yourself that you got a graduate role right away, so is this all really needed? The pace and scale of change in the number of students going to university and the number of graduate jobs available makes this work hugely important and more so than it ever has been before.

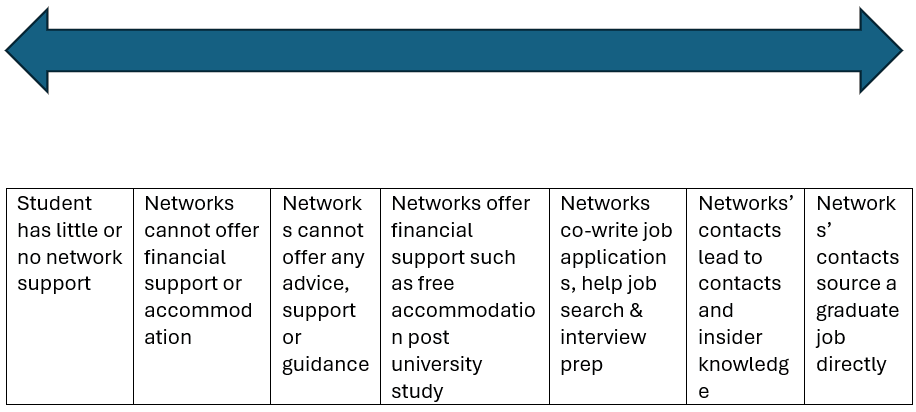

To continue this discussion, the second scale I wish to introduce below is based on students’ social privilege (or social capital) which gives certain students advantages over others when applying for graduate roles. For example, some of our students will be from demographics with more societal privilege than others (in various ways, recognising also that identities are intersectional), which gives them implicit advantages when applying for roles. Some students also come from backgrounds of financial, educational and parental-support privilege where they are exposed to support networks to help them get on the job market. Other students are not exposed to such privileges, although often come to university having heard the societal promise of going university being an automatic ticket to getting graduate job.

end of the scale of social capital and privilege is an extreme with regards to securing a graduate role. A student studies any degree, and their relational networks (e.g., parents) are able to source them a placement, a graduate role, and a mentor, all at ease without any applications. This student in reality is actually quite rare in most universities, but let’s continue with this employability privilege scale thought exercise. Next, we have a student whose relational networks are managers in white-colour office jobs, who can co-write and proofread their job applications, help them navigate the job market and even do interview coaching. There’s nothing wrong with doing this – I think we all do all we can to help our family, but it’s important to reflect on this in relation to our role as university educators alongside employability. Going further along the scale, perhaps towards the other end of less privilege. We have lots of widening participation students, whose networks may not be in hiring manager roles and who do not have the knowledge to coach them through the graduate job market. Consider further, of course, how other societal disadvantages play into these effects of lower social capital as outlined above.

When considering what to embed into the curriculum to address this manifested social inequality in the post-university experience, it’s useful to think about what can be structured in to try to move students further up this scale. We can’t quite offer the furthest end of the scale – a graduate job on a plate – but we can embed opportunities to practice job applications and interviews (and, importantly, receive feedback). Activities such as ensuring all students know how to write a personal statement to meet a personal specification, how to write a graduate CV, and how to answer interview questions are all hugely worthwhile when seen in light of the above scale. In addition, having knowledge of the diverse changing job market and industries available to our students, where often students may only be aware of the jobs they see in the media and are visible in society.

What do you mean knowing the job market?

When you ask a child what they want to be when they grow up, they say ‘Doctor’, ‘Teacher’, ‘Fireman’, ‘Taxi Driver’, because these are roles visible in society. When you ask a teenager what they want to do, they perhaps say roles that are still visible but through media, such as ‘CSI Investigator’, ‘Lawyer’ or, dare I say it, ‘Social Influencer’. When asking a student, it may not be that different to a teenager, where they may only be aware of the professionals showcased in the media. Most graduates’ jobs are actually invisible in society for our students, with many based indoors, or even ‘working from home’, so roles such as a ‘Cloud Engineer’, ‘Account Manager’, and ‘Scrum Master’, are completely unknown to students. It is therefore important to alert students to and de-mystify these roles and pathways available to pursue. Finally, placing emphasis on confidence and soft skills development is equally important for interviews and wider job securement success, from how to navigate a networking event through to email and social media etiquette. The list goes on, but I hope this provides a good selection of things to consider and with which to begin.

Conclusion: So what do we prioritise embedding?

The short but perhaps less palatable answer is we need to do a lot and I recognise and appreciate the tensions I presented at the start of this blog. However, although the graduate labour market is healthy, there is a lot of graduate competition (with some helped more than others, as the second scale highlights), and nationally, all universities are working on how they can improve their Graduate Outcomes. I believe embedding employability should be a structured and core part of the degree programme for the reasons I’ve outlined– and not an add-on optional workshop. And in consideration of the current attendance debates in higher education, many have come to the conclusion that if we want to make ‘structurally unavoidable’ employability – we must build it into not only the timetable but also summative assessment. Please see the readings below for further ideas on the great work going on in this space and next week, I will explore what might draw our students to class to engage with such learning.

Tom Lowe has researched and innovated in student engagement across diverse settings for over ten years, in areas such as student voice, retention, employability and student-staff partnership. Tom works at the University of Westminster as Assistant Head of School (Student Experience) in Finance and Accounting where he leads on student experience, outcomes and belonging. Tom is also the Chair of RAISE, a network for all stakeholders in higher education for researching, innovating and sharing best practice in student engagement. Prior to Westminster, Tom was a Senior Lecturer in Higher Education at the University of Portsmouth, and previously held leadership positions for engagement and employability at the University of Winchester. Tom has published two books on student engagement with Routledge; ‘A Handbook for Student Engagement in Higher Education: Theory into Practice’ in 2020 and ‘Advancing Student Engagement in Higher Education: Reflection, Critique and Challenge’ in 2023, and has supported over 40 institutions in consultancy and advisory roles internationally

Readers:

Advance, 2025. Employability, Enterprise and Entrepreneurship in Higher Education. Available at: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/teaching-learning/employability-enterprise-and-entrepreneurship-higher-education

Lowe, T., 2023. Embedding employability into the curriculum: five recommendations to improve widening participation students’ graduate employability. Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education, (26).

Higher Education Policy Institute [HEPI] 2023. Humanities education is a UK strength: New report shows it is a mistake to set up a Humanities vs STEM contest. Higher Education Policy Institute [HEPI], 30th March 2023. Retrieved from: https://www.hepi.ac.uk/2023/03/30/humanities-education-is-a-uk-strength-new-report-shows-it-is-a-mistake-to-set-up-a-humanities-vs-stem-contest/#respond#

Pitchford, A., Owen, D. and Stevens, E., 2020. A handbook for authentic learning in higher education: Transformational learning through real world experiences. Routledge.

Tomlinson, M., McCafferty, H., Fuge, H. and Wood, K., 2017. Resources and Readiness: the graduate capital perspective as a new approach to graduate employability. Journal of the National Institute for Career Education and Counselling, 38(1), pp.28-35.